(That time I moved to Japan alone at 21)

Preface:

This is the beginning of a new segment on my Substack—one devoted to travel, throwing yourself out of your comfort zone, and following your dreams. It will encompass: solo excursions, impulsive detours, heartbreaks and heart healing in moments spent learning to belong to myself in new places.

I start here in 2019, with Japan: the first country I explored on my own.

Cheers to making a home of yourself.

Walking home was the best part.

My apartment was cradled in a quiet suburban nook, tucked away from the bustling streets nestling three lively shopping centers, in a peaceful subdivision called Abeno. Four flights of stairs up to the top floor was my little home, secured by a heavy, faded pink metal door.

You’d have to lift your foot a bit higher to enter through the doorway. Once in, the bed’s to the left, the wardrobe at the foot, and beside it a tiny kitchen with a mini fridge and microwave. Through an elevated door next to the kitchen was the bathroom. On the right of that, an exit to a tiny balcony fit for drying clothes. The property also provided a wooden table that faced a large window gifting me a generous amount of sunrise light, along with a vibrant view of the neighborhood rooftops.

Rent was ¥52,000 per month, which at the time, was equivalent to approximately $400 USD.

Ten or so minutes out of the subway, I’d often end up at the 24-hour corner store—the infamous 7-Eleven, or as I’d come to call it, the konbini, the Japanese shorthand for “convenience” store.

It was no mystery why this chain (specifically in Asia) held such a beloved place in the hearts of many, romanticized plenty by tourists. Spotless and stacked full of goods, the rows of every aisle were blemished with color and variety from top to bottom at every hour. It didn’t matter if I’d stop by at 8:00 pm or 1:00 am. The irashaimases were undoubtedly always cheerful, the floors consistently mopped, and the pot of oden at the register always hot.

I’d serve myself a steaming cup of the dashi broth on colder nights, avoiding the eggs and radish in my pursuit of fishcakes and tofu. Other times I’d help myself to a prepackaged roast beef and wasabi sandwich, or sometimes I’d get a thing of inari, or a bag of earl grey tea cookies, if I’m feeling sweet.

It was quick and easy and clean.

Everything in Osaka was.

I arrived at the Kansai International airport at 9:40 am on a Thursday morning.

Prior to my pre-arranged pickup, I’d been required to have at least ¥200,000 in cash, have a telephone card in hand, and have a man named Masatoshi on speed dial. He’d been given my flight details and would be waiting outside of JR Namba Station to take me to the apartment I’d selected. I’d opted out of using a baggage delivery service given that Masatoshi would have a van out front. Getting the telephone card was easy, though I’d also prepped myself to alternatively utilize the phone booths. ¥10 would give me thirty seconds. ¥100 would give me three and half minutes.

After baggage claim, I made my way outside to a line of airport limousine buses, keeping my eyes peered for platform #11 bound for JR Namba. A ¥1000 ticket for the next bus and a fifty minute ride to the station later, I met Masatoshi. His English was less than conversational, and my Japanese far less than ideal, making the car ride stew in what could have only been an (expected and) accepted kind of silence.

The space to breathe had finally given me the much needed time to digest the fact that I had not only just flown 5,431 miles across the Pacific to a country I’d never been to, but I’d found an international job online a year ago, took a six hour road trip to Los Angeles to interview for it (lasting nearly nine hours), worked three part time jobs while finishing my Bachelor’s degree to save up, packed my bags, and moved alone.

When I was someway and somehow fed the notion that it was possible to begin my adulthood post-grad life in Japan, I took it upon myself to apply to three different language companies. Most companies offered stipends and loans, or even paid for your flight and found you an accommodation. Upon further research, I’d learned that the majority of them were primarily only English-speaking. Some programs were school owned. Some were corporate. All that anyone needed to do was apply, have a few references, a letter of recognition perhaps, and to be able to participate in lengthy skill assessments and scenarios in an interview session with other candidates.

Navigating Asia by myself at twenty-one was, needless to say, a strenuous yet exciting pursuit every day. I did, however, find it easy to make friends. Call that luck, call that God, call that me, but I was blessed.

I met B on the street while I was on my way to the ward office.

When you move to Japan, within the first two weeks of your arrival, it’s critical that you visit the local city ward in order to register your address and obtain your zairyu, or residence card. This was a particularly terrifying endeavor, since I’d found anything that involved waiting around in governmental agencies intimidating. Especially being a gaijin? With questionable Japanese ability? But it had to be done. So before flying out, I’d printed out a Google translated blurb of what I needed to accomplish at the city ward to give to the reception desk.

Little did I know it would end up being useless.

Maybe I’d looked lost or naive—probably both—because I’d been a couple of blocks away from the office when a man on the street flagged me down and asked me, in English, if I was looking for City Hall.

I’d quickly, and very trustingly, exclaimed wait—yes.

And it was like a firecracker.

“I just got back from there. Did you just move here? Did you need to get your residence card? How’s your Japanese? I’m fluent, I can take you there and translate for you. I don’t mind waiting around, I don’t have anything going on today. I’m B.”

I answered all of his questions, and he would continue on, persistent in helping. And just as he had offered, he stuck around in the office with me. Any potential feelings of loneliness that could have crept up on me during my first week dissipated, and I’d started thinking about how the only way to ever combat uncomfortable waves of isolation was by being open to what may come one’s way.

Leave room for miracles, they say.

I learned that B had, coincidentally, just moved into the same building as me, and would be living in the apartment directly beneath mine. He’d just gotten hired at the same company, so we’d be in training together for two weeks upon our start date. He’d also, as if there would never be an end to surprises, moved from California. He was around five or so years older than me, and was a well-known Youtuber with a pretty massive following on social media.

We got along rather well.

He seemed to like drowning the silences with his voice, had a whole list (both touristy and niche) of places he wanted to visit before starting work, and needed someone to take his photos. We both won a friend, some sightseeing company, and a hand in documenting our ventures.

Amemura, short for Amerika-mura, was a radiant and Westernized district off of Shinsaibashi, often glittered with the most diverse groups of locals living in Osaka. Street-style icons, lolita teens, grungy skaters and businessmen alike, international folk that have integrated into the community, would all be seen socializing on public steps and under lamp posts. Many sought refuge in bottles of Asahi and servings of kobe beef in one of the many yakiniku that lined the streets. Brick walls were adorned with graffiti, and the shops were eclectic, flashy, vintage. The thrift stores reminded me of the secondhand retailers my friends and I would explore on Haight and Valencia in San Francisco.

After yet another day of solo exploration in mid-October, I took the Midosuji line headed for Senboku-Chuo and hopped off after an eight minute ride. It would be another five to walk over to what was otherwise known as the “American Village” to meet with A and H for melon pan and shopping.

I found comfort in furniture stores.

Decorating my apartment was a craft that brought immense joy to my solitude.

There was something about house decor emporiums that gave me an inexplicable sense of home; and I’d built a habit of frequenting many of the shops throughout the city, compiling small goods and trinkets to take back to my place. Whether it be a new comforter, vase, ceramic plate, incense, string lights, or knick knacks, I found that the bits of furnishing would elevate my space tenfold. Maybe it was the Westernized touch to the materials, or maybe it was just that it mimicked the details of my old bedroom from my parent’s home.

It almost made it feel like I was taking remnants from a continent away to store with me for safe keeping.

Of all the markers of modernity that made Japan feel so advanced, their public transit ranked top tier.

B taught me how to purchase what became my daily essential and best friend—an Icoca card, a reusable clipper card for Osaka’s subway system.

I rode the train five days a week, usually taking the Midosuji Line out to work, where I would then transfer over to the Hankyu Line off of Umeda to head to Kyoto. On the way home, I’d take the Tanimachi Line, since I felt safest in that station during the night. Some people would refer to the routes by color; Midosuji being red, Tanimachi purple, Yotsubashi blue. Repetition made it easier to build routine, and transportation was always accessible, efficient, and affordable.

The trains themselves were exemplary, from the floors to the cushioned seats, washed windows, leg heaters. The practiced punctuality embedded into the culture could be reflected in the reliability of their transit system, making it so that if anyone had ever been late to anything, it must have been their own fault.

The stations varied from ward to ward. Some were objectively more happening, while others in residential areas remained peaceful. Stations like Osaka City in Umeda, Namba, or more populous Metropolitan areas had higher-end infrastructure full of entertainment: rows of quality department stores, dessert cafes, restaurants, bars. Rather than take a train to a station, you could simply go underground and saunter to the next stop while maneuvering through the subway bazaar, pastry in hand, on foot.

During my days off, I’d embark to the unfamiliar, for fun.

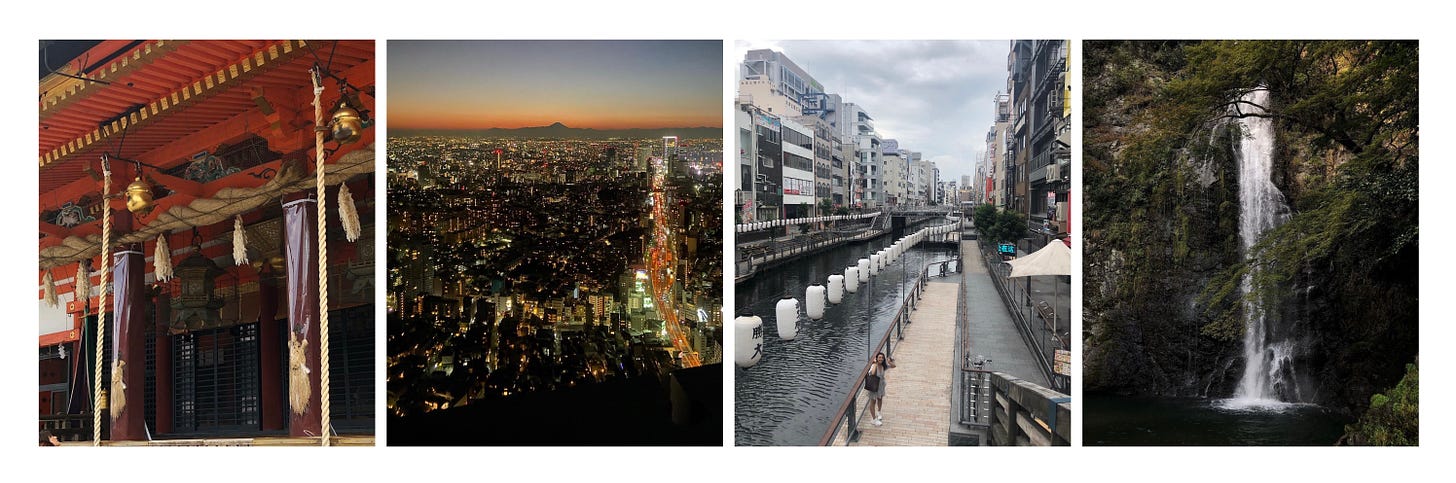

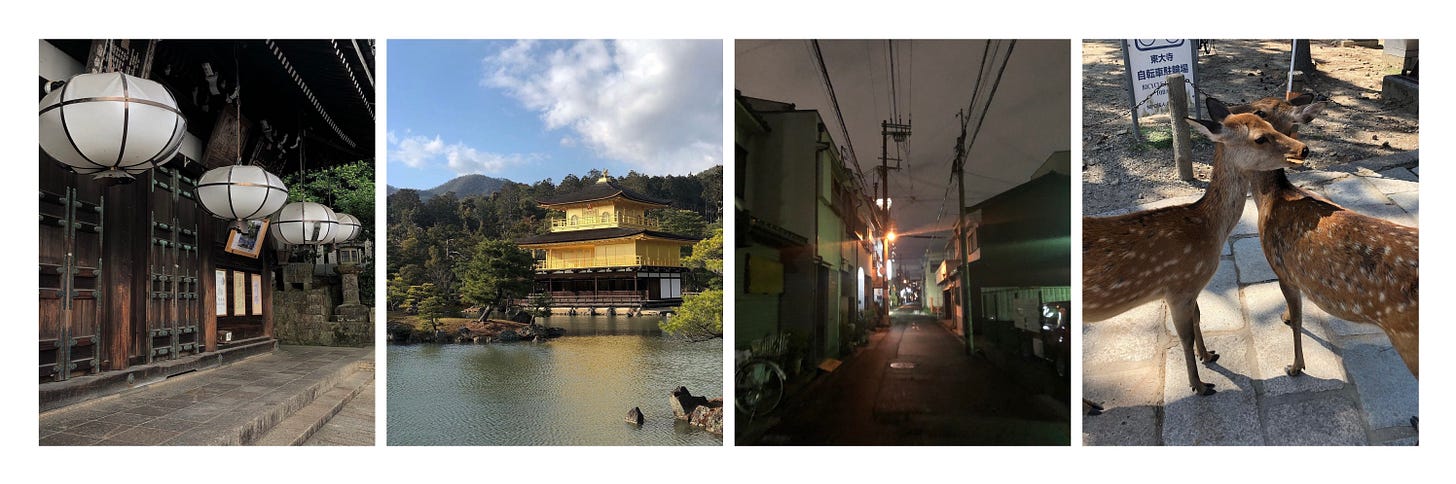

Since I had visited the urban side of Kyoto a dozen times for work, I made it a point during my free days to touch more of its historic and spiritual corners. I wandered through some of the most famously known shrines, noting their elaborate elements: the endlessly winding gates of Fushimi Inari, the towering wooden veranda of Kiyomizu nestled inside Higashiyama, the reflective symmetry of Ginkakuji, the Golden Pavilion.

Solo days wandering became immersive studies in form, balance, and intention.

Kifune’s linear stone staircase framed by towering cedars and the ornate rooflines of the Byodo-in temple introduced me to a new way of seeing space: not just as something to move through, but as something to feel within nature’s confines.

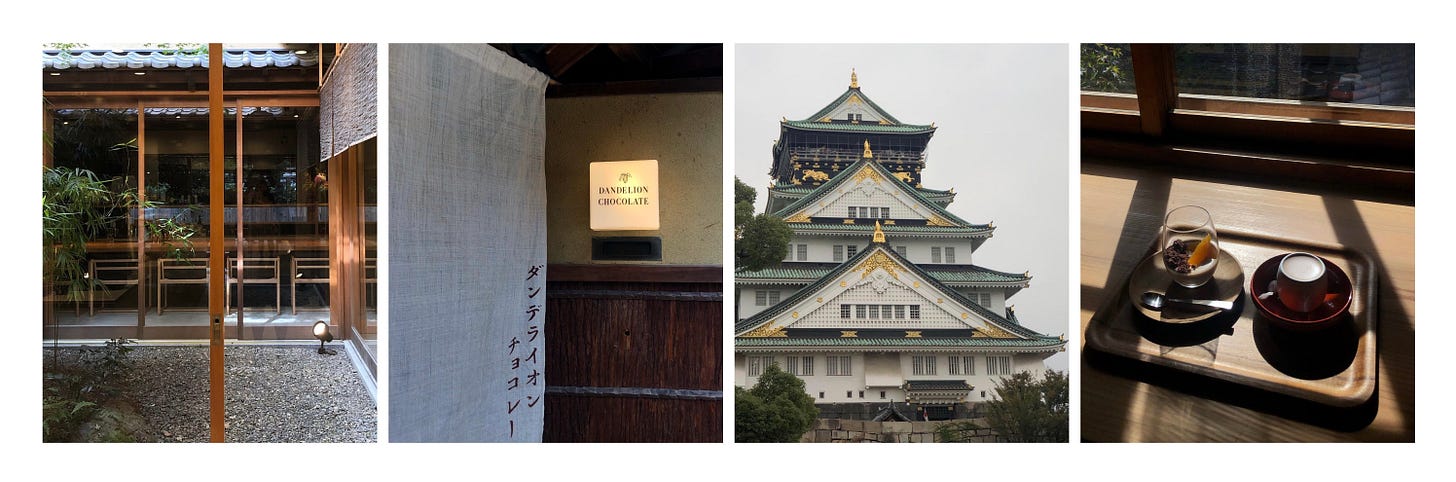

Experiences here planted the seeds of my fascination with architecture and design. Shaped was my personal taste ever since: an affinity for the organic, the fluid, minimalism that held warmth, and homes that evoked stillness. I photographed everything that pleased my eyes or elicited any kind of emotional response from me.

Even outside of those nature-drenched escapes, I found beauty in the architecture of my everyday, extending far beyond Kyoto.

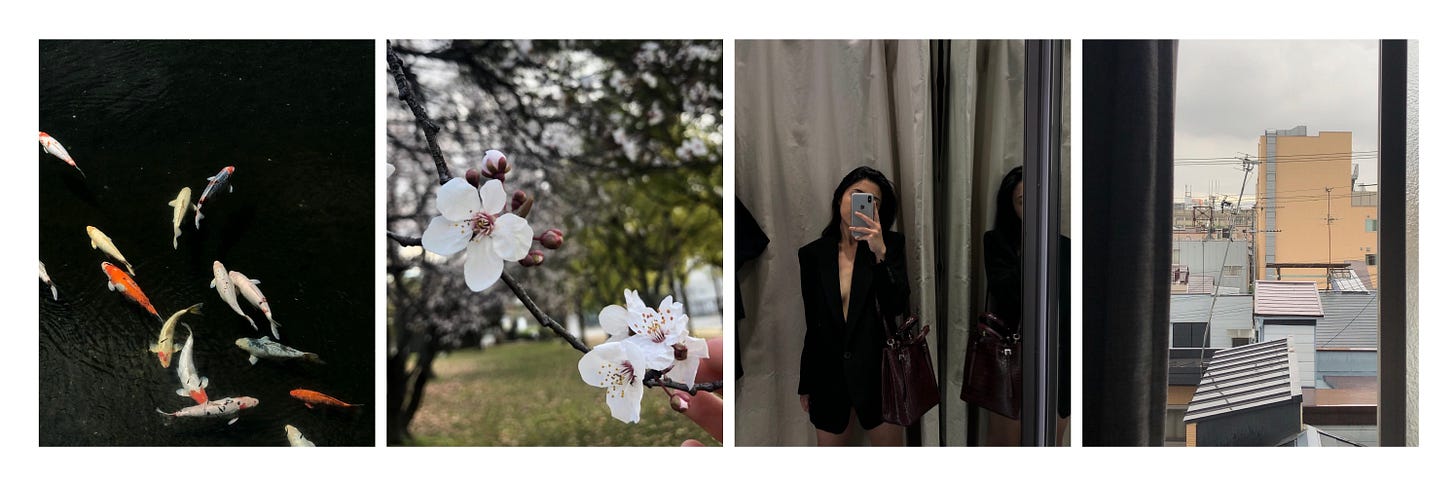

I went to Nara with M, A, H, and J where we roamed the Deer Park on the way to the Todaiji Temple. I commuted to Himeji countless times, and took a peek into its castle before one of my shifts. I chased waterfalls, hiking solo in Kobe to reach Nunobiki Falls and trekking through the misty greens of Minoh with A.

On self-prescribed holidays, I traversed Osaka, exploring with less urgency but no less affection. I’d return often to Dotonbori Bridge, Osaka Castle, and Takatsuki. I strolled through Den Den Town, cluttered with its cosplay shops, cat cafes, and collectibles. M raved about Den Den Town.

He had also convinced me to get an annual pass to Universal Studios Japan, which was a short trip from my apartment. By our fourth visit, I’d already made my money back.

In the Autumn when trees turned flaming red, F came to visit me with her mom. They’d traveled through Europe just weeks before, already on a vacation high. Together, we went to Bishamon Temple, laughed through Don Quixote for their absurd and delightful, enjoyed the Pom Pom Purin Cafe, and indulged in wagyu.

I noticed that each city I’d stepped foot in honored both pace and pause. Every space felt deliberately carved out. Temples sat beside skyscrapers, bamboo flanked subway stations, water trickled behind stores selling hand shaped ceramics.

Nature and structure never competed and instead, collaborated. It made me think differently about what made a space worth being in. My day to day walks on city streets or along river beds shaped the way I perceived homes, how I decorated, what I documented, what I looked for.

How I started to notice the light through a window or the way certain plants could saturate wooden furnishings or soften rooms—it began in those shrines and forests, in between drinks of sake and bandaging blistering feet. These were the moments my taste began to take shape.

B took me along with him to the Nishiki Fish Market after we’d hiked Mt. Inari toward Summer’s end. I’d treated myself to a shell of rich, creamy sea urchin. Uni was one of my favorite luxuries back home.

Though certain dishes warranted my hesitation (surprisingly nothing raw and slimy, and instead those which were lathered in sauce), I never shied away from cuisine. There was a long list of delicacies I had set out to try and form an opinion on.

Osaka was known for their okonomiyaki and takoyaki—both I found to be more enjoyable when shared. Things too saucy for me typically turned me off. Mayonnaise, especially, unfortunately. (Sue me.) Stands serving both were every couple of blocks, the aroma perpetually permeating the streets.

I enjoyed experiencing the solitude of a meal in a booth at the famous Ichiran’s. The ramen was solid, but not necessarily life-changing. A topnotch dish I’d consistently have for a mere ¥400 was gyudon. B had shown me two chains that would never fail: Yoshinoya and Sukiya. A bowl of rice with a whopping load of thinly sliced beef? For $3 USD? Insanity. The katsu curry rice I’d tried on my lunch break once was also a winner in my book. Special mention to omurice topped with melted cheese and wagyu.

I’d also learned that “nigiri” and “sashimi” were not normal words to use to order sushi in restaurants. The “nigiri” I would order back home to specify raw fish on top of a small wad of rice was solely just “sushi” in Osaka; indicating that we, as a Westernized society, have associated “sushi” instinctively with rolls—the California, the Dragon, the Caterpillar, Alaskan, Lion King, Cucumber, Spicy Tuna rolls—none of which are served nor even existed in Osaka. There was only nigiri, and that was called sushi.

Then there were sweets: macerated strawberries (though I never cared much for tanghulu), chewy dango (yum), warm taiyaki (red bean was my weakness—), kinako mochi (—soybean powder, too.)

Grocery shopping was humbling.

Navigating aisles in search of familiar staples proved one of the more difficult of tasks. Soy milk existed, but required hunting. Oat milk, a fantasy. Granola and oatmeal were rare gems I only managed to find in a specialty foreign import store. Translation: outrageously priced. Right next to fruit. Watermelon was a signifier of opulence, worth $150 USD. A bundle of grapes, $30.

Needless to say, my kitchen experiments were limited. I stuck to what I knew: boiling water. I became a hot pot connoisseur out of pure necessity.

“I heard Umeda has the best nightlife,” H mentioned while pulling herself a slice of pizza. We were grabbing dinner after thrifting in the Chūō-ku ward. We’d spent the evening with A, discussing all the important things that brought us, as young women, together: coworker gossip, astrology, exes, men. I met her my first day of work. She was hard to miss. Beautiful, with light eyes and lighter skin, curly dark hair, tall. She was a pescatarian, a proud Leo, a Canadian. Later, she’d invite me to a drag show.

“I’ll probably tap out after this,” I replied. I loved spending time with them, but I was also quick to recognize when my social battery needed charging.

“Are you sure?” H was keen on persuasion.

“No, I get it, it can be so tiring sometimes, not only needing to walk everywhere, but needing to try to communicate with everyone. It’s so much energy,” A was keen on understanding.

A was fair-minded and grounded. She was the type of person who could read people easily, and the verbal commentary (if there were any that followed suit) would be something of compassion rather than of judgment. I liked this about her a lot. I trusted her easily.

She was also quietly adventurous.

She’d traveled to Hokkaido on her own during the holidays, detailing the horrors of her expedition with me over wine and vegan ramen one day in the Springtime. It involved losing her wallet on the mountain, being in a small city with barely any English-speakers, forgetting a phone charger, and getting lost amidst it all. But since it’s Japan, and there was an internalized understanding of property and respect, her wallet was returned to the nearest police station with everything intact.

Another elite aspect of the culture was the collective belief against stealing. Belongings being returned to individuals, or being left alone, was an honorable norm I’d witnessed daily. Laptops and cellphones would be left untouched on tables in cafes and restaurants while restrooms were used. Bicycles were parked unchained. Purses would be left alone or returned to lost and found. Someone could leave their airpods on a bench one day, and guaranteed, they would still be found there after a week in the same spot.

Despite the expected, massive relief had still washed over A. And regardless of the challenges and the inevitable breakdowns, she hadn’t regretted the trip in the slightest. She was, in fact, planning her next excursion.

“I’m thinking Korea,” she shared, pulling her blonde hair back before slurping her noodles.

I admired her spirit. It broadened my scope of what was actually possible.

I loved hearing about the simplicity of traveling from (various) Asian country to (various) Asian country. Since costs were so low, it wasn’t unheard of for people to fly out for a day or weekend trip. Another girl we’d worked with had just flown to South Korea solely to shop on a random Friday.

Suddenly the realm of my own capabilities expanded.

I started checking roundtrip prices here and there, debating on flying solo around and out of the country. Costs would be as little as the equivalent to $52 USD.

I wondered why more people weren’t doing this, carrying this mindset to each tomorrow I was granted.

I rode the shinkansen to Hakone on New Years Eve.

I was en route from Tokyo, where I had spent a week familiarizing myself with the atmospheric differences. Standing as the most populous prefecture in Japan, the urgency that washed over its crowded streets reminded me a lot of New York, differing greatly with the overall relaxed air I’d acquainted myself with living in Osaka.

Kanagawa was much different. It was slower. Quieter.

I’d found a traditional bathhouse inn located near the mountains of a small district in Hakone. The Sengokuhara district was known for its open-air hot springs, or onsens. I had decided that this was how I wanted to ring in the new year. My coworkers were partial on visiting the bathhouses in Osaka, though a fair number had critiqued its participants. The more acclaimed spots were unfortunately the more conservative, meaning tattoos inhibited entrance. However, if small enough, those could be bandaged. On the other hand, the onsens practicing inclusivity were typically bombarded with tourists.

For my first experience, I’d wanted something more novelty, more exclusive.

The ryokan I’d found was called Susukinohara Ichinoyu, and it was everything I could have ever imagined it to be. The wooden, dimly lit, traditionally designed abode was cloaked in greenery that draped along the windows of my room. On my balcony was a private hot spring with the view of the mountain and its surrounding nature, the only sounds being of moving water, rustling leaves, crickets.

Since it had been New Years, the inn provided specialty dining courses for both the evening and morning, known as osechi-ryori. The food was served in small servings packed in tiny boxes like a collection of colorful assortments either complementing the other or working as a palate cleanser. Each carried symbolic meanings: good health, good fortune, long life.

Ichigo Ichie (一期一会) was a Japanese proverb I’d read about by Héctor García, translating to: one time, one meeting, for this time only, once in a lifetime. To live with Ichigo Ichie was to show up fully, because any moment, exactly as it was, would never come again.

I came to Osaka to teach, and yet each day I’d spent in Japan had shown me there was so much left for me to be taught, about ways of living and journeys less traveled, about motivations and people, philosophies and joy.

I started questioning whether life was shaped by milestones or if it was actually formed by the quiet middlegrounds. Each decision I’d ever made felt more and more sacred. Each moment, monotonous or unique, was unrepeatable. This morning, this walk, this friendship—anything that I chose would only further my devotion to living a life I made beautiful by attention.

On my walk back home to Abeno, I took a moment to stop by 7-Eleven and perused the aisles, open to trying something new.

loved this to bits! from all the details of your days to the glimpses of the people in your life. how these characters are given life just by how you describe them! i can imagine everything… if you wrote a book i would read it.

I enjoyed how evocative this piece was, full of descriptions of daily life and apparent mundane things, which i have come to learnt are the things we carry with us when we leave a place, this, as someone who has moved their fair share. Right now I’m in my early 20s thinking about all the possible paths I could choose, and the line about your capabilities realm -not your possibilities realm- broadening is something I’ve been pondering and needed to read. Looking forward to reading more notes